- Home

- Rokdim Nirkoda 105

- And They Shall Beat Their Swords Into Plowshares

Interview with Yoav Ashriel, by Judith Brin Ingber,

first conducted in 1972 and updated in 2006.

Reprinted from Seeing Israeli and Jewish Dance.

Edited by Judith Brin Ingber. Wayne State University Press 2011. Pages 150-154.

Copyright© 2011 Wayne State University Press, with the permission of Wayne State University Press.

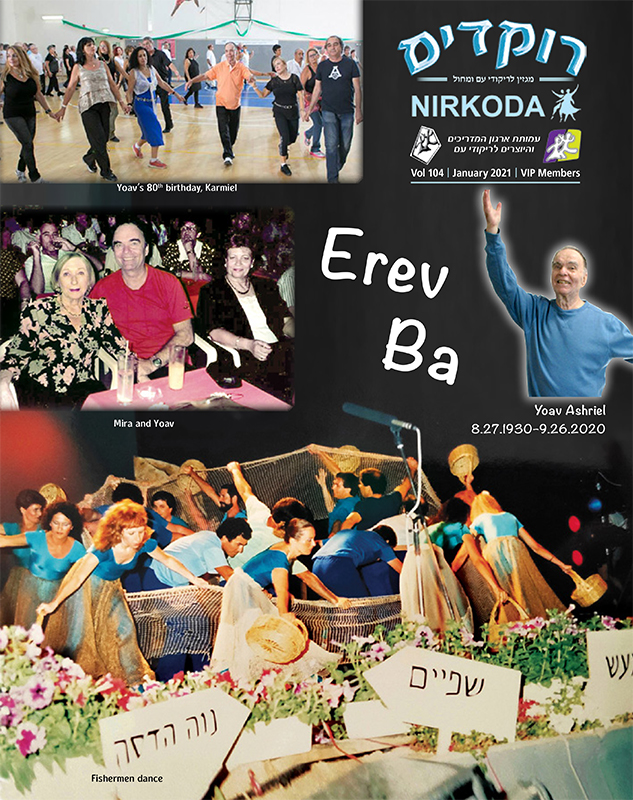

Yoav Ashriel was born Yoav Glicksman on August 27, 1930 and was raised on Kibbutz Ramat David, Eretz Yisrael. He married his dancing partner, Mira (who died in 2008).

Ashriel was one of the first creators to develop from the Histadrut-sponsored folk dance courses, although he became independent of the established system and was the first to run his own workshops for a fee, in turn encouraging others who worked outside the establishment, such as Eliyahu Gamliel, Ya’ankele Levy, Benzi Tiram, and later Shlomo Maman, Roni Siman Tov, and Avi Peretz. He taught and directed folk dance groups for the army, for the Tel Aviv municipality, for festivals, and for performances. His dances have wide appeal, and some that would otherwise have been downplayed in secular Israeli society are surprisingly successful, with themes about the beauty of the Sabbath (probably, Likrat Shabbat [Welcoming the Sabbath]) or shtetl life. He was such a successful dance leader that his outdoor evenings were the first to attract enormous crowds. His work was recognized in 1992 with the Cherished Folk Dancer Award from the Teachers Organization of Folk Dance, Va’ad Ha-Poel of the Histadrut, and the Ministry of Education and Culture. (By Judith Brin Ingber who wrote up the following):

For me, folk dances are created for the enjoyment of the dancers. At least that’s how it has worked for me. I always made dances for my friends.

I’m from Kibbutz Ramat David, and I didn’t know anything about dance until I was 17. I was a kibbutz kid who worked with the cows. At our kibbutz we didn’t dance a great deal, but we sang. Once someone had given me an old accordion so I was one of those who accompanied the singing.

I was fairly good in sports too, so when the kibbutz received an invitation to send a couple to a course for folk dancing, it was natural that I was one of the two sent. At the course I met Gurit Kadman, who had come to teach us five dances. We were youth from many kibbutzim, and I remember we all loved it. Gurit opened my eyes. I remember exactly what she taught: Hora Agadati, Sturman’s Im Barazim, a sherele, Ze’ev Havatzelet’s U-banu Batim, Bo Dodi, and a rondo. It took a full day to learn them (now our experienced folk dancers could easily learn that in an hour) and afterward each couple went back to their respective kibbutz and taught what was learned. I played on my old accordion and found myself directing the kibbutz in dancing. I was immensely excited by it. Then I joined the army.

I was in Nahal, the part of the army that trains youth who intend to set up new border kibbutzim. Ze’ev Havatzelet came to start a performance group within Nahal, and he asked me to lead a course for folk dancers in Nahal. I asked how could I, when I barely knew the dances myself, but he was my officer and he said, “Do it,” so I began. What developed was a course for soldiers to become folk dance leaders organized on the same principle as my own first introduction: each unit of Nahal sent a couple to learn the dances, and they in turn taught their own units.

I made a group from the Nahal soldiers and started creating dances for them too. We appeared at the Dalia Festival in 1951. We were eighty dancers. We used the newly created sickle and swords symbol for Nahal in our dance. I think this made a big impression to see young men and women holding swords that turned to plowshares and scythes as in the biblical prophecy. That year Shoshana Damari sang “Ta’am Haman,” which became very popular, and I decided to make a dance to the music which meant so much to us. My dance La-midbar I created in the same way, using a popular melody. I knew that what the dancers loved they could execute well, and what is deeply felt and also expressive of the dancers can become material for folklore.

I left the army and became a folk dance leader for the Ha-Poel group of Tel Aviv, working there for seven years.

I never taught without creating dances and making performances. Maybe I’ve done sixty or seventy dances, [This was true in 1970 but by the time of this interview update in 2006, he had created some 200 dances] but they’ve always been for my group or my friends, not because of a certain holiday or for a special event. In 1953 I did Ez Va-keves [Goat and Sheep] to a very popular song by Mattityahu Shelem with a Mizrahi feel, so beautiful to me, and somehow it had the atmosphere of the fields. The words made a distinction between shepherds and shepherdesses, so in the dance I separated the men and women. I think it was one of the first dances where we didn’t do everything in unison. But it expressed something to us and therefore it worked.

Dances that are fluent, with one step leading you to the next, with music that catches you, are well loved. I think Sara Levi-Tanai’s are especially like that, even if she only did three that became folk dances. They are a fantastic gift to us. Rivka Sturman’s dances are also fluent and they make us want to dance. I think they are irresistible. Each moment counted, and each movement mattered to us because it spoke to us, which unfortunately is not what’s happening in 2006 [this was the year of updating the original interview with Ashriel from 1972].

Israeli folk dance has changed. First it was European flavored and then Oriental spice was added. I actually learned the Yemenite step from Rahel Nadav [she created dances based on her own Yemenite background] at a Shavuot festival, maybe in 1949. I remember it was so hard for us to understand, for we were used to such big kicks and jumps. That’s the way it has changed from the beginning for me—from something bold and bravura to a quiet joy of the heart. You know we Jews are a very serious people and we don’t suddenly get up and jump. I think the dances must be felt with reason, then with so much feeling inside, it has to come out and be expressed in the movements. It’s wrong to think all our folk dances are fiery ones.

The reasons for dancing are the key to the dances. It is too contrived to believe the way to get people dancing is to reconstruct old Jewish festivals. We live in a modern society and our dance must reflect this. I think folk dances become popular according to sentiment, not because of rules of teaching or programming or even because of the intentions of the creators.

Once, though, I purposely decided to create something with a quiet, calm atmosphere. Circle dances had always meant joyful, strong steps, and the form of the couple dance usually allowed for more peaceful, gentle movements. But I wanted the whole group to dance in a different mood, so in 1960 I took a lyrical popular song and I created Erev Ba. At first it was considered too sentimental, but it’s still a favorite, and the whole circle dances in a gentle way.

The more I got involved, the more I realized we needed teaching tools. There weren’t records but Fred Berk in New York was wonderful, and he encouraged me to start recording music and writing down the steps. I thought I could make clearer explanations than what was available in written form from the Histadrut. At Kibbutz Shefayim I offered a course and 300 came. We used film and we did serious work, and we talked about stage craft, and I didn’t allow bickering or talking on the side and everyone got respect.

By the 1970s, Ashriel said, the dancers in folk dance had changed.

Those who do folk dance do it less spontaneously. Often the dancers have much performing experience, and certainly they know a large repertory. They might also know jazz, modern, and even ballet, unlike those at the beginning of the folk dance movement. I think I was considered a traitor for wanting to learn ballroom, jazz, and modern dance when I studied with Ruth Harris [an American who came to Israel in the 1960s and was one of the first taught jazz] and others. Today I think all this training can make the folk dancers demand more complicated dances.

And forms change from what they once were. Maybe the original intent of the circle dance was to be done shoulder to shoulder, like Hora Agadati, but our climate is too hot for such close proximity, so with experience, horas and fast dances have opened up in space.

Ashriel speaks about going against the grain.

I was criticized for making a dance of love in a circle instead of in a couple form, or creating a circle dance that incorporated turns which I was told will never work (now look how many there are in our folk dances!), dropping hands when everything had been danced with participants clasping hands. One of the other changes today, and I don’t think it is a bad change, is the fact that rock and pop are entering into our folk dance. International folk dances, especially the Greek, are popular too. In our summer programs of folk dancing in the city square of Tel Aviv, sponsored by the municipality, you see our youth coming to do both rock and folk dance.

It started as a result of a trip I made to Spain, outside of Barcelona. I saw how people danced outside, and I thought the city square in front of Tel Aviv’s city hall would be perfect. So, we started the summer sessions there, and by 1970 we had thousands coming, and buses of tourists would arrive just to see Israel dancing.

One can’t escape from the fact that music on the radio and all around us has changed, but I think this combination adds to the folk dance itself. It reflects today’s values. Very few village bands with accordions exist now—we have tape recorders, well, now its computer hookups to loudspeaker systems in the town squares like the Tel Aviv program I mentioned. I think that in the end, no matter where people dance, be it in the kibbutz or the city, if there is good music, then more dance is stimulated.

I use all forms rock, pop, international, traditional, as well as our own Israeli folk dance as I learned it and I believe it’s all for the good. We can’t freeze all the folk dances. In the beginning Tova Tsimbel made beautiful dances at Dalia, and we had almost an unbearable excitement there. I won’t forget what it was like when I came with the army and we put down our blankets on the earth to try to sleep. Now, what is all that jumping and circling round and round on the floor of a huge sports arena about? It doesn’t seem to say anything. But still, I know it’s about change, because folk dance is something that’s alive and continues to grow.

Comments

התראות