- Home

- Rokdim Nirkoda 105

- His First Encounter with Folk Dances had Changed His Life

His First Encounter with Folk Dances had Changed His Life

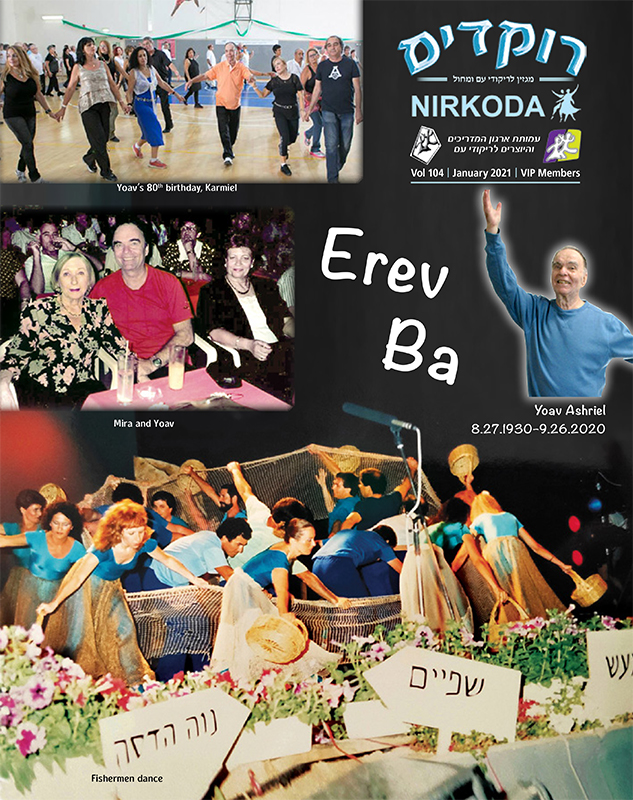

A conversation with Yoav Ashriel 23 years ago

- Translation: Alex Huber

It was in January 1997 when I met Yoav Ashriel in Tel Aviv. Well, actually I met him already at least 15 years before, when I attended around 6 to 8 of his “Hishtalmuyot”, dance sessions for dance instructors, in Kibbutz Shfayim from around 1980, when I still lived in Jerusalem. Since I had moved to Munich (Germany), got a hold of Yoav’s phone number, called him, introduced myself as a dance instructor now living abroad and asked him if he would be interested in meeting me. At first, he seemed reluctant, questioning me if I could name one, just a single one of the dances he created. Of course, I could, and I proceeded to mention close to a dozen – such as “Erev Ba”, “Mi Yithneni Of”, “Bo be-Shalom” and “Klezmer”, all dances which are part of my beginners’ repertoire.

We met, on a sunny day in a café in Tel Aviv for close to three hours, talking about “God and the world” and certainly about dancing; my life, and much more important, his way to Israeli folk dancing. Since I recorded our conversation, I can easily repeat Yoav’s words. He was born in August 1930 in Kibbutz Ramat David. His, then 94-year old mother, Hanna, was born in Poland, still lived there, and his Austrian-born father was already deceased. Yoav vividly described life in his home kibbutz in the days before Israel’s independence: Electricity did not exist yet at the kibbutz, and paved roads connecting the kibbutz to the “outside world” were still a dream. As a result, there was hardly any direct contact with people outside the kibbutz.

In 1947, Yoav was just 17 years old, when the kibbutz secretary approached him. The secretary received from “somewhere” a letter which offered a regional 3-day hishtalmut for “Rikuday-Am” under the leadership of Gertrude Kaufman (alias Gurit Kadman, 1897-1987). Gurit was born in Leipzig (Germany) and moved to Palestine in 1920. No one ever heard about “Rikuday-Am” in this remote kibbutz. However, since Yoav played the accordion and was also a good athlete, the kibbutz secretary decided that Yoav would be the right person for the course and registered him together with a 15-year old girl comrade (unfortunately I forgot to ask him for the name of that girl). Yoav‘s initial resistance was quickly given up for the prospect of three days away from school.

Arriving at the course location, he was informed that participation was only possible from the age of 20. However, due to the late hour, a return trip on the same day was out of question. As the youngest dancing couple by far, the two youngsters were finally allowed to take part in the entire course and distinguished themselves as the most talented and best dancers. They learned eight dances, including dances like “Kuma ECha” or “Eim Ba’Arazim”. There were not many more dances at that time, as Yoav remarked smugly in a subsequent clause. This was probably due to the fact that 1997 there was already an unmanageable number of dances and choreographies. For sure, back then, we were not able to foresee the flood of dances a quarter of a century later.

Yoav Glicksmann openly declared that his first encounter with folk dances had changed his life. He instinctively felt that this new form of dance expressed the longing of the pioneers in Eretz Israel to a united Jewish-Eretz-Israeli people. He began to organize dance performances for Jewish holidays in his kibbutz. At that time there were no “Ulpanim”. So, he attended at irregular intervals advanced training courses hosted by the labor movement’s “Histadrut.” When Israel became independent in 1948, Yoav was drafted into the Nachal army division. His duties included, among others, the organization of all activities in the field of “Rikudei Am”. While serving he met his future wife Mira. They had two children. With modest pride Yoav told me that at one of his Nahal dance performances David Ben-Gurion was present. At the end of the performance Israel’s first prime minister inquired about the name of the leading dancer, who, of course, was Yoav himself.

In 1950, while still serving in the military, Glicksmann presented his first dance named “Ta’am Ha’Man”, choreography much discussed at that time. Yoav intuitively countered arguments such as a “waltz beat” would not be suitable for a folkdance or that Yemenite steps in a couple dance to classical Central European music were definitely out of place: First, the music to “Ta’am ha-Man” was in 3/8 time, so there would be no similarity to a real waltz, and second, he was aware that many Jews in Israel had European cultural roots as well as Yemenite.

In his opinion, the homogeneity of the young Israeli society could only be reflected by the fusion of cultural elements. These are simple facts which one may emotionally support or not, Yoav added.

He could not really choreograph at all, as my interlocutor disarmingly continued. According to Yoav’s own words, dance steps and movements come “just like that.” I tried to interrupt Yoav’s flow of words at this stage, since I believe that choreographies need more than just a bit of intuition. In vain! Yoav continued: Israel, at that time, was still separated from external influences, certainly due to the limited means of communication as compared to today. In this respect it was, as seen in a historical context – quite understandable for a people to create its own and therefore also new folklore. Consequently, it was not surprising that many of his early dances like “Ez Va’Keves ” or “Pashtu Kvasim” (both 1953) and “Ha’Kormim” (1955) corresponded to the down-to-earth, agricultural pioneer ideal. For he had grown up in this environment, as did Matityahu Shelem (1904-1975), a founding member of Kibbutz Beit Alffa (1922), who composed the three mentioned dances. It is noteworthy to mention that also others like Rivka Sturman (1903-2001), Lea Bergstein (1902-1989) or Tzvi Friedhaber (1935-2001) used Shelem’s music for their choreographies.

In 1951, after being discharged from the army, Yoav turned his back on kibbutz life and settled in Tel Aviv. He changed his surname and Hebraicized Glicksmann into Ashriel. “Glück” in German means “luck” hence Ashriel or “osher” in Hebrew. At the time, with the active support of Gurit Kadman, he founded the largest Harkada (dance session) under the umbrella of the trade union’s sports club Ha’Poel Tel-Aviv. “Rikuday-Am” was not really a way of making a living at that time, and if so, only modestly and poorly. Yet, “Rikuday-Am” soon became his main occupation. Since no support was to be expected from any kibbutz for such a free spirit, for additional income, he started working as a secretary for the Histadrut, Israel’s trade union. In addition to his efforts to advance regular Harkadot in the Greater Tel Aviv area, he visited South Africa, Hamburg and Kassel in Germany in 1968. He also came as a choreographer to the International Youth Festival in Vienna in 1959.

Yoav‘s dance activities, at that time, were mainly in the field of stage choreographies. Already in the early 50s he managed two dance troupes. Many of his today’s better-known circle dance choreographies entered the general folk-dance scene via the stage.

He placed special emphasis on new dance elements, such as the Arabic influence in “Dal’unah” (1959) or different dance sequences for men and women in couple dances, such as in “Ez Va’Keves” (1953). Hotly disputed within the dance establishment at the time was “Erev Ba” (1960), which is now considered a classic. Some of the counter-arguments back then were: Such a slow and romantic melody can be nothing else than a couple dance. Moreover, it contained too many twists and turns, and in general: What does the topic of “love” have to do with genuine folklore! With obvious satisfaction he noticed, that Rivka Sturman’s choreography for a couple dance to the same music was not accepted by the dance community. Arie Levanon, the composer of the song, thanked Yoav personally a few years later for the successful realization of his song. As a composer he still receives royalties. Royalties which as we know do not exist for choreographers until today. Other classics followed, such as “Hora Medura” (1963) or “Kor’im Lanu Lalecheth” (1972).

In 1976 Yoav founded together with Tamar Alyagor (1924-2013) and others the “Irgun Ha’Madrichim”. He did not go into details but told me that because of some “fundamental differences of opinion” in how to lead the organization he soon resigned. Just a few years later, in 1981, he started to organize his first “Hishtalmut” – where I met him first.

All in all, looking at the variety of Israeli folk dances, as they are presented in the mid-90s, one simply must filter out “the good elements.” Since even among the old dances of the 1940s, for instance, we can determine good, less good, perhaps even bad ones. On the other hand, at least according to Yoav during my meeting with him, it is practically impossible to enjoy the present without the folkloric roots of the past. Which was certainly a clear side blow against a certain part of the dance participants, who want to exclusively concentrate on “modern dances”, the “latest hits”, so to speak. Can we nowadays talk about “Rikudei Am” at all or would a new term be necessary? Such as the term “Israeli recreational dance” which, for example, was introduced long ago in the USA. Yoav concluded this topic with the statement that ”in a liberal society, however free, cultural diversity may ultimately be more important than the enforcement of ideological boundaries.”

We came slowly to the end of our dialogue. I turned his attention to an article about him, which was published in January 1978 in the American folk periodical “Viltis”.

Back then, Yoav argued that only those dances should be recognized as Israeli folk dances, which were directly choreographed in Israel. Which in the 1990s would clearly exclude such names as Moshiko Halevy, Moshe Eskayo, Israel Yakovee, Danni Dasse, Shlomo Bachar, and many more. And what is valid for dance should also be applied to music. However, Yoav soon realized that practice had overtaken theory: Only some good years after he choreographed “Ba’Aviv At Tashuvi Chzara” (1972), performed in Hebrew by the Nahal vocal group, he had to realize that the original version of this song was sung in French by the well-known French-Armenian singer, Charles Aznavour. “I would like to be the last person who wants to oppose by force this development, as it exists today”, Yoav literally expressed twenty years later. “Clinging too much to certain, yet controversial, provisions would, without any doubt, undesirably hinder the development of the Rikudei Am scene in Israel”.

In 1997, Yoav placed emphasis that dance steps and sequences are performed in a fluid and natural way, so that dancers simply enjoy dancing. All along Yoav rejected the so-called “championships” or any similar competition in the field of Rikudei Am. Because those who absolutely want to distinguish themselves can do so in the well-known performance groups. He regularly met with a few colleagues, people such as Shlomo Maman, Avner Naim, Tuvia Tishler and Roni Siman-Tov, in order to evaluate the current situation of Israeli Rikudei Am. In the mid-90s Yoav saw his main task as supporting young choreographers in their work.

With the sun disappearing at the horizon our meeting was about to end. He left me a few older black and white photographs as a reminder. Unfortunately, this was the last time that I met Yoav Ashriel who I personally consider as one of the most important personalities in Israeli folk dance.

Comments

התראות