- Home

- Rokdim Nirkoda 117

- Israeli Folk Dancing in Japan

Israeli Folk Dancing in Japan

The Experiences of a Dance Instructor from Germany in the Land of the Rising Sun

Although each of our valued readers knows approximately where Japan is located, i.e., in the Far East, more specific geographical details are largely unknown. For example, Japan lies much further south than is generally assumed. Tokyo is at the same latitude as Los Angeles or, in Europe, at the same latitude as Cyprus. In principle, Japan is an island state with four main islands: Hokkaido, Honshu (the largest island and considered as the mainland of Japan), Shikoku, and Kyushu and around 430 other inhabited islands. In 1945, four islands in the north, namely Habomai, Shikotan, Kunashiri and Etorofu, were annexed by the then Soviet Union (from 1992 the Russian Federation) without any historical claim. Japan, administratively divided into 47 prefectures (“ken” 県), is only slightly larger than Germany and corresponds to approximately 85 percent of the land area of California. In terms of population, Japan has 126 million inhabitants, one and a half times that of Germany, the largest country in Europe. On the other hand, Japan’s population is much smaller, only around 38% that of the United States, but it is more densely populated.

To foreign observers, the distances within the country on the north-south axis may also be surprising: From Wakanai (Hokkaido) to Naha (Okinawa as part of the Ryukyu Islands) the straight line distance is almost 2,500 km (or roughly 1,550 miles), compared to Buffalo (in New York State) at the border with Canada to Miami (in Florida) with “only” 2,235 km (1,389 miles).

Although it can be assumed that Israeli folk dances are an integral part of most of the international folk dance circles spread across the country, the center of Israeli folk dances in Japan is clearly in the greater Tokyo area, which has a population of 38 million inhabitants, followed by the two neighboring cities of Osaka and Kyoto (the latter being the capital of Japan until 1868).

Yaron Meishar, editor of the periodical, “Rokdim-Nirkoda”, reported extensively on his trip in autumn 2002 in issue number 61. Accordingly, Gurit Kadman z”l, born in Leipzig in 1899, must have visited Japan already in the 1950s, followed decades later by other well-known Israeli names such as Jonathan Gabay z”l, Tuvia Tishler, Shmulik Gov-Ari, Yankele Levy z”l and David Edery. During his trip to Japan, Yaron was looked after by Toru Kashima z”l. Not much is known about him. Basically, he spent the years 1987-1991 in Israel, studied not only Hebrew, but also completed successfully the Israeli Folk Dance teachers’ course in Tel Aviv, and was so enthusiastic about folk dancing that he eventually became a member of the performance troupe, “Gvanim”, based in Rishon-Letzion and under the direction of Ilana Segev and Tuvia Tishler.

After his return to Tokyo, for many years, Kashima-san led a small dance group within the premises of the local JCC, as Michiko Gough remembers. There must have been an Israeli folk dance group within the JCC for many years already before 1990. The leader at the time was named Ruth. In the early 1990s, the dance circle consisted of about ten to twelve Jewish and six to eight Japanese participants. The Japanese participants were recruited from an international folk dance group called the “Arima Recreation Club” under the direction of Satoru Suganuma (菅沼 知), whose courses consisted of half international and half Israeli folk dances. Suganuma-san was an enthusiastic supporter of Israeli folk dance and attached great importance to the members of his group experiencing a genuine Jewish and Israeli atmosphere for the sake of authenticity. When Ruth returned to Israel, an Israeli replacement could not be found. Therefore, Kashima-san, as an qualified Israeli dance instructor was the natural choice to succeed her and he was also paid by the JCC for his dance instruction.

As Michiko reports, Toru’s lessons did not always run smoothly: An Israeli woman, who had previously taught in Sydney, was a guest at the JCC dance courses for about six months. Once when Toru taught a couple dance with her as a partner, there must have been an open conflict between the them about the exact sequence of some of the steps. Also, as is often observed elsewhere, Israelis habitually have problems appreciating and accepting the expertise of those who come from “outside”; that is, Israeli folk dances belong to Israelis and therefore Israelis must always know better. From 1995, Michiko danced regularly once a week under the direction of Kashima-san. She noted with regret that under the new Japanese leadership, the Jewish participants gradually stopped coming, so that within just a year, the JCC dance course went from being a Jewish-Israeli-Japanese event to being purely Japanese. Michiko emigrated to Australia in 1998. There, she first taught in Perth; a few years ago, she founded her own dance group in Hobart (Tasmania, Australia; see “Rokdim-Nirkoda” issue 112). In 2019, Kashima-san died from the effects of prostate cancer.

Greater Tokyo area – Akiyoshi Komazaki (駒崎 章喜), Email: za9y-kmzk@wave.plala.or.jp

Today in Japan, if you want to dance exclusively Israeli folk dances, you cannot get past Akiyoshi Komazaki, who, as a member of the “Irgun Ha-Madrichim”, arranges everything for anyone coming from abroad. This is especially true for Israeli folk dance choreographers, who happen to include Japan in their holiday itinerary. In this case, they should contact him at least three months prior to their arrival. As practice proves, almost everywhere in Japan, communication in a language other than Japanese is quite difficult, even though English is still the most widely spoken foreign language. I myself was lucky enough to have found extremely valuable support. Thankfully, over many weeks, if not months, Michiko Gough was extremely helpful to me, especially in keeping in touch with Komazaki-san via email. Without her, many things would have turned out to be certainly more difficult.

During the time I had planned to stay in Japan, Akiyoshi was able to organize three workshops in and around Tokyo, each of which was scheduled to last between two and a half to three hours. I was surprised by his request to only present dances I myself had choreographed. For sufficient preparation, Akiyoshi requested the video material more than two months in advance. This included the dances: “Yam Adonai”, “Ha-Aviv Tzochek”, “Shacharut”, “Rak Et Kolech Eshma”, “Debka he-Chalil”, the couple dance “Or Ha-Ganuz” as well as my latest choreography, “A-Salam Aleikum”. Of course, all of these dances are available to view free of charge on the ROKDIM website. At the workshops, participants were able to purchase teaching materials Akiyoshi had prepared (such as music and video clips of the dances), while t-shirts with the logo of the “Israelisches Tanzhaus” (ITH, Munich) were quickly snapped up.

My first workshop took place in Tokyo on September 27th, 2024, with a group of over sixty participants. Like everything in Japan, the event ran exactly on time, which should not be a problem for “yekkim”, like the author of this article. The audience was not made up just of dancers with a special focus on Israeli folk dance. Members of the “Folkdance Federation of Tokyo” also appeared, including its chairman, Tsuneo Matsumoto (松本 恒男). For the couple dance, I was provided with a local partner who had practised the dance perfectly beforehand having used the provided teaching video. Kazuko Bando (板東 和子), representative of the “Folkdance Federation of Japan” in the Ibaraki prefecture north of Tokyo and head of an all-Israeli dance group in the same prefecture, was available to me as a translator. After the workshop, I was able to conduct a short interview with all of the people mentioned above.

Until his retirement, Matsumoto-san (1948) worked full-time as a computer engineer. As a student, he first came into contact with international folk dance at the age of about 20. For reasons that he can no longer remember in detail, for example, he already preferred Israeli dances to Romanian dances. When those responsible for the “Folkdance Federation of Tokyo” heard of Tsuneo’s retirement at the time, they asked him to take over the leadership of the organization. Now, they figured that he would have had enough time for new tasks. Since then, with this new assignment, he has been keen to increasingly incorporate dances from other cultures, particularly in view of the changing age structure of the dancers. According to him, the development of Israeli folk dances over the last two decades has shown that many of the new dances are simply too complex for the majority of today’s folk dance audience. There are simply too few new dances, for example, with the level of difficulty of “Yam Adonai”. In addition, most of the dancing takes place indoors, which he feels limits exposure to those outside of the groups, especially younger people. In order to attract a younger audience to participate, he tries to organize outdoor dance events.

Komazaki-san (1941) originally came from the Tokyo district of Asakusa (浅草), known for Tokyo’s oldest-established temple Sensō-ji (金龍山浅草寺). As is common in Japan, high school students are required to attend additional courses in the afternoons after school, and so he joined an international folk dance group at his school. He particularly remembers Russian, Israeli and “Alpine” dances (Austria). From 2006, while organizing a workshop with Dudu Barzilay, he began to study Israeli dances in general more intensively. Dudu Barzilay has since visited eight times, followed by others such as Yaron Ben Simhon, Gadi Bitton, Avi Levy, Nurit Melamed, Jack Ohayon, Eyal Ozeri and Avi Peretz. What he particularly likes about Israeli dances is the diverse music, such as in Benny Levy’s “Tzel Etz Tamar”, which he sometimes believes has similarities to some Japanese melodies. He currently runs two weekly dance courses, Tuesdays and Thursdays, with about twenty-five participants each, and another course every other Sunday.

Hiroko Sakurai (櫻井 広子, 1962) originally came from Saitama Prefecture, north of Tokyo. She first came into contact with mainly Russian folk dances while studying at college, even though at the time, the dance lessons always started with the same Israeli song: Rivka Sturman’s “Kuma Echa”. After finishing her studies, getting married and looking after children, Sakurai-san took a break from dancing for about ten years. Around 2005, she finally founded her own international dance group called “Cherrie” (チェリー). [There is no other word in Japanese for “cherrie” as a fruit.] The group includes around thirty particants and meets regularly on Friday mornings to dance international dances. The afternoon course features Israeli dances only. Each of the two-hour courses costs 300 yen and together both cost 500 yen (about US$ 3.25 or ILS 12).

Kazuko-san (1955) originally comes from Tokushima (Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s four main islands). For her husband’s professional reasons, they moved to the district town of Tsukuba (つくば市, about 270,000 inhabitants, Ibaraki Prefecture, north of Tokyo), where, at the age of about 30, she joined an international folk dance group. Around fifteen years later, Bando-san moved to Ryukasaki (also in Ibaraki Prefecture) and, lacking other dance opportunities, simply founded her own dance group there. Since then, for twenty years she has been teaching international folk dance every day. Her Thursday group particularly prefers Israeli dances. Above all, for example, they like them because they allow for much more personal feelings to be expressed in contrast to Bulgarian dances.

In principle, current Israeli dance groups, as far as they exist, can only be found through Komazaki-san. As was repeatedly mentioned by him, one of the main problems in Tokyo is finding a hall at a reasonable price. Unlike in many countries in Europe, Christian institutions do not show any support for such activities. In conclusion, Israeli dance groups are somewhat rare. This is also confirmed by Rabbi Scheer from Japan’s JCC, who is currently not aware of any such courses. The cultural attaché at the Israeli embassy in Tokyo, Ms. Gil Markovitch, was equally unable to help me. So, it is no wonder that even on the Internet, when searching for, “Israeli folk dance in Japan”, there is practically nothing to be found. Due to the lack of a possible longer stay in Japan, it was not possible for me to find out whether Israeli folk dancing is practiced in one or more of the “kibbutzim” in Japan. According to a report in Ha’Aretz magazine on June 8, 2023, there are said to be around twenty such agricultural-established communities in Japan that are based on the Israeli model.

Osaka – Akira Nishikawa (西川哲), Email: np5.vino@gmail.com

In “Rokdim-Nirkoda” issue 115, Naftali Chayat and Orly Shachar reported on their experiences in April 2024 at a dance evening in Osaka; with 2.7 million inhabitants, it is the third largest city in Japan. According to the report, Israeli dances are only a small part of an otherwise much larger international repertoire led by Nishikawa-san. Due to considerable language barriers, communicating with Akira beforehand via the Internet was not always easy. He himself started dancing over 30 years ago in a university group and, in 2019, he took over the local dance circle, which had been active since 1956, after the previous group leader suddenly died. The group, with an average of ten participants, meets once every week on Wednesdays for two hours. The monthly fee for each two-hour evening is 2,000 yen (about US$ 13 or ILS 47). The participants range in age from 30 to 70. For new dances, he relies on visits to Japan by Israeli dance masters or choreographers, although since the outbreak of the Corona virus he has also used “harkalive” by Ilai Szpiezak as a source, albeit rather irregularly.

The date I had suggested (of course a Wednesday, specifically September 25, 2024) could not be kept because – purely by chance – a choreographer named, Silvia Macrea, had already been invited for the same evening. She is considered a specialist in Romanian folklore and, among other things, leads the professional performance group, “Cindrelul – Junii Sibiului”, founded in 1944 by her father Ioan Macrea. Despite multiple requests, unfortunately, Akira could not provide any photographs of himself or his group.

Kyoto – Imai Hideki (秀樹今井), Email: h_imai_fd@zb3.so-net.ne.jp

Kyoto was the capital of Japan for over 1,000 years (794-1868) and today, it is the 7th largest city in the country (and, in my opinion, the most important city to be visited in Japan). Hideki-san leads an international folk dance group called the “Sagano Folkdance Group”. Repeated inquiries were not answered by Imai due to “lack of time”.

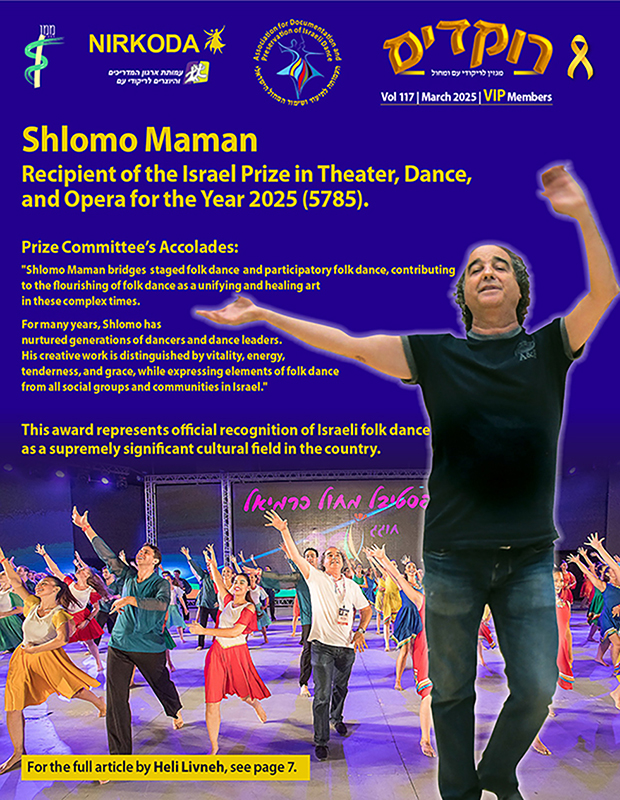

On my way back home, which included another stop in Okinawa, often called the Hawaii of Japan, I was once again invited to Taipeh (Taiwan) by An-Hsiang (余安祥) and Bi-Ying (詹璧瑛), as already reported in “Rokdim-Nirkoda” issue 113. At the regular Thursday meeting, I taught Shlomo Maman’s “Shamayim” and my dance, “A-Salam Aleikum”. For Friday’s beginners “plus” class, my choices were “Yam Adonai” and “Ha-Aviv Tzochek”.

Comments

התראות