- Home

- Rokdim Nirkoda 103

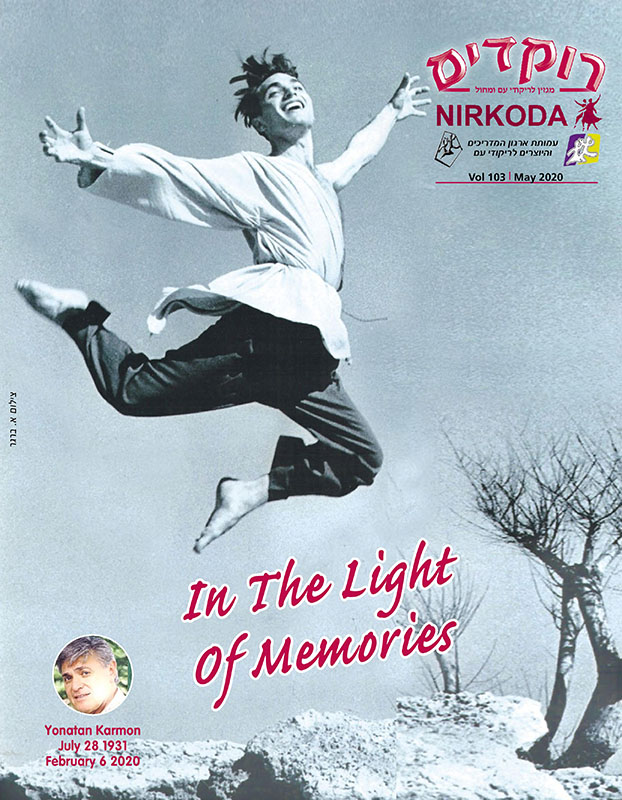

- The “Karmonic” Language and Spirit

![]() Is there an Israeli dance? Is there a local character to Israeli folk dance? What makes our folk dance Israeli dance?

Is there an Israeli dance? Is there a local character to Israeli folk dance? What makes our folk dance Israeli dance?

These and similar questions have been asked for many years by scholars, academics and the general public. It is known to all that the people of Israel were gathered from all over the globe. Did the arrival of Jews from Europe, Africa, America and Asia produce something in common? Something that can be identified as local? Is the local Arab and Druze population, with all their nuances, also part of this common identity? What is their impact on Israeli dance?

When I think of Yonatan Karmon and especially about the work of this talented choreographer, all those questions and wondering come up again.

Yonatan Karmon immigrated to Israel from Romania in 1944, a 13-year-old who left his home and escaped on the children’s train from Nazi Europe. He left behind his family and home (also see Ofer Aderet’s obituary in “Haaretz”, February 14, 2020), together with his brother, to an unfamiliar country, with a very different culture.

Upon arriving in Israel, Yonatan gave up his European identity almost completely when he deleted his previous name, Yonel Kalman and became Yonatan Karmon. An important point in formulating his identity as an Israeli choreographer, not only because he lives and works in this place (Israel), but with a genuine desire to be an Israeli, to belong; so too was born the desire to create something unique to this place (Israel).

How do you define Israeli dance? I’m unworthy. Although I have written about Israeli dance for Kol Yisrael for 20 years and from time to time for this magazine – “Rokdim-Nirkoda”, I find it difficult to define the local dance. Is the fact that most of the dances for the stage and especially the folk dances are choreographed to Hebrew music and lyrics? Of course not!

What is an “Israeli step” in the country in which a Romanian step sequence for a Hora (from the Romanian Hora), the Yemenite step, and even the Debka step from the Arab dance have infiltrated into the daces? – Apparently there is none, and yet if I ask myself who do I think is the “most Israeli” choreographer we’ve had, I would certainly think of Karmon.

First, there is the “Karmonic Spirit” – enthusiastic, joyous and sometimes even story. Karmon‘s dances are easy to identify: he has a “dance language.” In art – nothing is more important than a unique “language” and a beautiful thing for all creators in the various art fields: theater, music, plastic arts [e.g., sculpture and ceramics] and of course, dance.

Karmon‘s dances are, for the most part, energy-filled dances, rhythmic and full of the joy of dancing. If anything can be said about what makes it “Israeli” then there are the qualities – enthusiastic, happy and yes … even a little arrogant. Yes, yes, there is a certain “shvitz” in Karmon‘s dance, which means: “I’m here, you can’t ignore me”. What typified Karmon was a strong presence intertwined with a recognizable aspect of elegance.

Upon arriving in Israel, Karmon studied dance with Gertrude Kraus, Mia Arbatova and Rina Nikova. This classical foundation is found in his works even though it is not apparent to an “unprofessional eye”. It is there, and it is that special combination between the freedom of folk and the classical that makes his works unique.

Anyone who looked at this handsome man, with his sparkling eyes, his captivating smile, and his gorgeous locks of hair, would definitely say that this is a typical “Sabra”. Despite his being European by origin, he possessed the aura of a Sabra – a native Israel. His dances reflected both.

Perhaps the need for an Israeli spirit adds something that in our time is not considered “politically correct”. The intention is that Karmon loved and wanted beautiful dancers in his troupe. When I once asked him who, in his opinion, was “a dancer”? He replied: “A dancer needs to look good. As the singer’s tool is his voice, so the dancer’s tool is his body.”

It is not clear whether an “overweight” dancer could fit into Karmon‘s troupe, but surely Karmon‘s dancers had shapely and aesthetically pleasing bodies. In particular, Karmon was careful to maintain the body and, in this regard, of course, the worldview of classical ballet was continued.

He also emphasized eye contact between the dancers. In particular, this relationship is of course noticeable in the partner dances. For example, in the dance “Elem VeSusato the dancers look like “riders” on a horse. In the second part of the dance the “riders” move away from each other, but they still look at each other from a distance and then join and turn together and walk together. The gaze is very important in this dance, giving it the feeling of a strong relationship even in the sections where they dance (the riders) separately. In the dance “Me’Emek LeGiva”(the song’s title is “Shtu Ha’Adarim”, lyrics: Alexander Pen, music: Nachum Nardi), a similar structure can be seen although the movement is different. The couple is wrapped together and maintains eye contact even when the man releases his grip. In the next section the man “chases” the woman as she looks at him while running.

In fact, Karmon‘s dances currently danced by the public (http://bit.ly/331cttz) are part of the dance medleys he created for the stage and they “came down” to the dance floors, after their adaptation to dance classes (primarily by Danny Uziel) and are indeed “inalienable assets”. Let’s look at three more:

The most Israeli dance in my mind, and on a personal note, one of my favorites is “Haro’a Haktana” (“Haroa Haktna Min Hagai”), created in 1955 with lyrics by Rafael Eliaz, music by Moshe Wilensky). First, there the beauty of the dance in its simplicity. Almost all of the dance is built on the same “basic steps” – jumping on two feet and immediately on one foot, alternating right and left. When the dancers enter the center of the circle it is again with the same steps. This repetition, in various formats, is indeed reminiscent of a sheep that grazes in the pasture but also of the young shepherd who hops after it. In addition, there is the “Karmonic style” of raising arms that accompanies the action and enthusiasm for this motion.

Another important choreography, this time in the form of a partner dance, is “Orcha Bamidbar” or as it is popularly known, “Yamin U’Smol” (1954, lyrics by Ya’akov Fichman, music by David Zahavi). Karmon chose steps that were bending and low to the earth, the desert land. The steps seem to be wearily “carried away” like a man “carrying” himself in the desert in the heavy heat. A brushing step and then big, wide movements, a kind of “slow motion” that is possible in the heavy heat of the desert (as opposed to short, fast and jumping movements). A beautiful motif of the kneeling couple while turning their knees, like the Bedouin kneeling in the desert.

“Shibolet Basadeh” (words and music by Matityahu Shelem), is one more of the dances associated with Israeli folk dance. This dance features two of the most “fundamental steps” associated with the “Karmonic Language” – alternating between jumping on two feet and one foot (“Haro’a Haktana”, “Nad Ilan”), and “scissors kicks back” (“Al Tira”, “Haro’a Haktana “,” Elem VeSusato “,” Me’Emek LeGiva”) – this time it is danced in couples and is accompanied by arm movements that simulate sheaves of wheat moving in the wind. These examples prove Karmon‘s special view of the Israeli landscapes and the people within.

Karmon made sure to choose songs and motifs that tell the story of this country and its people and perhaps just as importantly, a loving look at this place that has been his home for many years.

Yonatan Karmon will be very much missed in Israeli folk dance and I will also personally miss him.

· Miri Krymolowski, art historian, who explores culture in Israel and around the world

![]()

Comments

התראות