- Home

- Rokdim Nirkoda 107

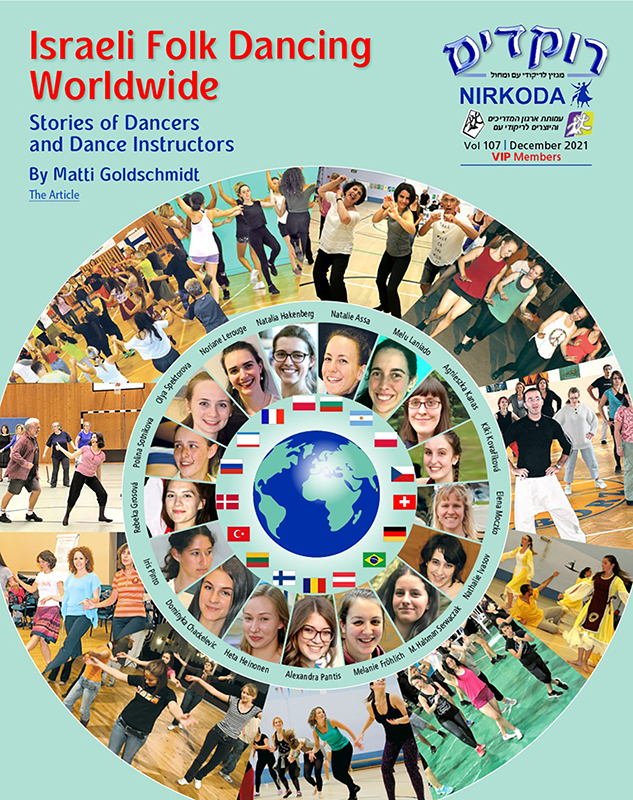

- Young Dancers from Around the World

Young Dancers from Around the World

The Story of the Girls of the "Younger Generation" in Israeli Folk Dance

I vividly remember a random meeting with Moshiko Halevy and Moshe Telem in Tzemach at Lake Kinneret in the early 1980s. Prior to Karmiel, this had been the place where the most concentrated Israeli folk dance events took place, those lasting over several days or so. The two were sitting somewhere on a lawn and I joined them for a casual chat. Towards the end of our conversation, they suggested that I come as a participant to a summer Israeli folk dance camp in England, where they were both part of the team of instructors. I could not hide my astonishment: Are they serious? First of all, I had never heard of any Israeli folk dance event outside of Israel worth mentioning. And secondly, why should I, living and dancing four or five times a week, travel abroad in order to participate in Israeli (!) folk dance? This idea seemed so strange to me, that I immediately told them that this will never happen. Just consider the costs of the flight from Israel and the fee for the camp. (Does anyone remember the additional exit tax of US $300 that we had to pay around this time for leaving the country?) Everything else would have been cheaper staying here in Israel – and definitely more genuine.

In short, the average Israeli folk dancer has no clue, or at least was clueless back then that Israeli folk dance is more than just alive outside of Israel. The only exception was perhaps their knowledge of Israeli folk dance in the United States – after all, a good dozen Israeli choreographers had established themselves there, mostly in New York and Southern California, including, (in alphabetical order), Shlomo Bachar, Dani Dassa, Moshe Eskayo, Danny Uziel, and Israel Yakovee. At the beginning, and for a number of years, their claim to be “Israeli” was not recognized by everyone in the land of their origin. Nevertheless, the Jewish population of the United States was large enough to engage and promote independently Israeli Jewish and/or Israeli cultural events.

Admittedly, at least in Europe, Israeli folk dance existed in the 1980s at best in the United Kingdom, France, and the Netherlands, albeit still on a relatively simplistic level, less so in Germany or Italy, apart from some almost insignificant clusters in other countries. However, this had gradually changed around 1990. Especially with the fall of the Iron Curtain, Israeli folk dance began hesitantly, but slowly to spread. Nowadays, one will find Israeli folk dancing in many more countries like Belarus, Bulgaria, Czechia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Russia, and Ukraine, albeit certainly not the magnitude of the better-known folk dance sessions in Israel or even in the United States. Some folk dance circles may have regular participation of only five dancers; others consist of five times as many and thus have formed a group of approximatedly twenty-five participants, which was already considered to be big. Often, the knowledge and dance skills of those can easily be compared with the most advanced folk dancers in Israel; here and there, to the disbelief of Israeli dancers who seem to claim a kind of a monopoly on “their” dances and that they simply must be better than those coming from abroad.

As in Israel, many of these dance enthusiasts abroad struggle to integrate young dancers into their groups, among others, and to possibly take over the activities of those who founded or revived existing dance circles, once the latter feels too old to continue. However, brushing the dust off a little bit, there seems to be a new generation of younger dancers in many countries who are willing to follow in the footsteps of the previous older generation. I found more than a dozen young dancers from over a dozen countries who were ready to tell me about how they found their own way into Israeli folk dance. None of these dance-related resumes is the same, but yet, in the end, they are somehow similar. And it is certainly noteworthy that not all of those interviewed are Jewish. Nevertheless, they without doubt belong to the worldwide network of Israeli folk dance – a situation the founders of Israeli folk dance, some eighty years ago, most probably never expected.

On the contrary, today in many European countries it is precisely the non-Jewish dancers who keep Israeli folk dance alive. Take Munich for example, the city where I live: With around 10,000 Jews, it has the largest Jewish community in Germany (Berlin is only in second place), according to member statistics, always keeping in mind that most Israelis and many thousands of immigrants from the Soviet Union with permanent residence in Germany are not registered with the Jewish Community Centers. And still, ninety percent or more of those who come regularly to the local JCC’s folk dance session on Monday night are non-Jewish. Without those people, Israeli folk dance would simply not exist, not only in Germany, but also in quite a few other countries due to the lack of regular dance sessions. Full of positive energy, with plenty of diligence and an unbeatable sense of mission, all those people mentioned here can be considered responsible for being part of the development of Israeli folk dance into an international phenomenon. And there are certainly many dozens more who were not included. One thing all those interviewed have in common: An above-average sense of mission (“Sendungsbewusstsein” = a sense of mission) to expand the magnitude, diversity and beauty of Israeli folk dance abroad, whether they are Jewish or, as in our case, mostly non-Jewish.

Natalie Assa, Bulgaria

Natalia was born in 1995 in Sofia, the capital of Bulgaria. In 1997 the family moved to Israel, but returned to Bulgaria about five years later. This relatively short time, however, was sufficient so that Natalie’s Hebrew is still fluent to this day. The year 2004 marks her first contact with Israeli folk dance when, at the age of nine, she started to dance in summer camps organized by the Jewish Community of Sofia. When she was 16, she became a member of the performing group of the local JCC; this was much more intensive in terms of work and repertoire and which, as she said, “inspired” her a lot. In in 2011, as a kind of reward, she joined a few other group members to drive by car from Sofia to a weekend session in Novi Sad (Serbia), led by Dina Dajč, and since then, in addition to the performing group, she has also regularly attended the weekly local dance sessions in Sofia.

All this was not enough for her; she then started to practice at home learning new dances on her own. In 2014, at the age of 18, Natalie moved to Vienna to study Economics. From the very beginning, she wanted to establish her own dance group. It was highly important to her to do her own teaching and also include the dance material she liked without being outvoted by others. The Viennese Jewish sports club “Hakoach” (Hebrew for “the strength / power”), founded in 1909 and Austrian national football champions in 1925, gave her the permission and the necessary infrastructure to establish her first regular dance session with fifteen to thirty people in attendence. Soon the rent for the hall became too expensive and she moved to a new venue, the “Jüdisches Institut” (= Jewish Institute), after its manager, Julie Handman, asked her to take over a vacant position. Now, she not only led a dance class for adults, but also for children in a Jewish kindergarten. In addition, she started teaching Hebrew to Jewish children. Nathalie’s basic idea was and is to bring, through the Hebrew language as well as songs, mostly sung in Hebrew, and their dances, some “Israelism” and thus new shades of color into a few Jewish diaspora communities.

She actually planned to create a performing group and hoped for the support of the Viennese JCC. However, because of Corona limitations, her plans had to be put aside for the time being. Like in many other European countries, all in-person activities ceased for close to one and a half years. In the beginning, dancing, and particularly Israeli folk dancing, was just a pleasant pastime, until it became an integral part of Natalie’s life as it is today. As soon as the pandemic started (March 2019), the situation became difficult dealing with such a volatile and constantly changing dance community as in Vienna. Natalie began to organize regular zoom meetings and several open-air dance meetings which were attended by up to 25 or even 30 dancers; by central European standards, this was quite an achievement. In October 2020, however, after having finished her studies, Natalie moved to Barcelona, Spain, where she found employment. Unfortunately, even after one full year, she still has not located the right infrastructure there to join, or even better, to establish an Israeli folk dance circle.

Melu Laniado, Argentina

Melu was born in Buenos Aires in 1995. From the time she was in her cradle, dance was part of her life in that her father, Raúl Laniado, and his two brothers had already been active in Israeli folk dance years before she was born. Thus, she started to dance, almost naturally, by the age of three in a group for children within the framework of the local JCC, playing dance-oriented games and even performing in small stage events. And, needless to say, she accompanied her father, the Israeli folk dance teacher, to his sessions and tried to copy the steps from others. Roughly ten years later she joined the dance group of Maccabi Buenos Aires, one of several Jewish organizations in the city such as “Hebraica” and “Ort Argentina”, among others.

After having turned fifteen, she became the youngest member of a two-year Israeli folk dance course for teachers under the sponsorship of “Seminario Rabinico”. It was her father, Raúl, who took care to have her admitted to this course, since normally participants have to be at least sixteen years old. During the weekly three hour course sessions, they learned a huge number of dances. In addition, the curriculum also included how to manage group dynamics and general psychology. The course also emphasized the inclusion of the so-called Israeli folk dance pioneer dances, enabling the graduates to leave with a balanced knowledge of older and newer dances. There are a dozen or more dance groups in Buenos Aires; the smaller ones with about fifteen dancers and the larger ones with thirty or more. A few times during the year they all meet together and then become a group of far more than a hundred.

At the age of seventeen, actually before graduating from that course, she already started to teach her own group, normally on Sundays, which she led until spring 2021, when through “Masa” (= journey), she went to Israel for a half-year program, created for young Jewish adults age 18-30. In 2019, for the first time, she visited a camp outside of Argentina, namely Machol Europa. The difference between camps in Europe and South America must be enormous. At Argentinian camps, the atmosphere is way more energetic. People will scream and sweat a lot, actually using the camps more as a sports happening than as a cultural event. Her current studies of Event Organization at the “Fundación de Altos Estudios en Ciencias Comerciales” (= Foundation of Higher Studies in Commercial Sciences) in Buenoes Aires will certainly help her to organize more Israeli folk dance events back home. Personally, Melu seems to live for Israeli folk dance, to spread the message of Zionism through dancing.

In April 2021, after Melu completed her studies, she moved to Tel Aviv where she works as a kindergarten teacher. Now, being in Israel, the land of unlimited Israeli folk dance opportunities, she dances at least four times a week, not only in Tel Aviv, but travelling as far as to the south (Ashdod) as well as up to the North (Haifa).

Agnieszka Kanas, Poland

Aguiezka was born in 1990 in Gdańsk (Danzig) and actually never had any thoughts about dancing during the first two decades of her life. In 2010, however, a friend of hers, Jolanta Kalisz, suggested that she join her to attend a (Roman Catholic) religious prayer group that tries to find a connection to God through dancing, adapted to Catholic rites – by the way, a very similar approach is used by the Hassidic movement. Therefore they chose mostly slower rhythms and dances, those with words were derived from the Bible. When Jolanta decided to take a break in 2012, the group dissolved. Two years later, Agnieszka met another woman, Dorota Nałęcz, who in 2003 had already founded another prayer group, which they later called “T’filati” (= my prayer). Agnieszka was happy to find a new possibility to dance. The group consisted of mostly five, sometimes seven or eight dancers and the repertoire of dances was relatively limited.

In 2015 Beata Krzywda, coming from Krakow, joined the scene and called her new group “Simcha” (= joy), which existed until 2017. This was the first time that a regular weekly dance course was established in Gdansk, that was not connected to prayer through dancing, but rather concentrated on the clear purpose of Israeli folk dance itself. This included a separate class for beginners, followed by one for those who are more advanced. Meanwhile, Agnieszka learned how to become updated with more contemporary Israeli folk dances through camps like “Polin Rokedet”, organized by the Hakenberg family, and several workshops organized in Warsaw by a group called “Snunit”, led by Monika Leszczyńska.

When Beata had to leave Gdansk, by coincidence, Natalia Hakenberg had moved to the city and founded a new group called Roztańczony Gdańsk (= Gdansk dances), which she led until 2019. Meanwhile, the above mentioned Dorota returned to dance, which gave her and Agnieszka, who studied management marketing in the maritime industry, the opportunity to take over this group. In other words, Agnieszka, who started without any dance experience entering the Israeli folk dance scene through prayer, became, in less than ten years, a group leader of two dance groups: “T’filati” with the focus on combining prayer and dance and “Gdansk Dances” as purely an Israeli folk dance circle. Together with Dorota, she participated in the last Course for Israeli Folk Dance Instructors (Ulpan) directed by Yael Yaakobi with Yaron Carmel providing instruction on teaching methodology. The aim of the course is to learn about Israeli folk dance “from the first founders until today”, “the history of Israeli folk dance as well as its development over the years”, dance techniques on how to create stage choreographies and even how to create your own Israeli folk dance. In August 2021, she passed the tests with 96 in theory, 95 in dancing and 90 in teaching. The dance she had to teach was Rivka Sturman’s “Shiboley Paz”, definitely not one of the easiest dances to begin with as an Israeli folk dance teacher.

Not only were Agnieszka’s friends surprised about the personal development she experienced through dancing the folklore of another country, with another religion and a strange-sounding language. Looking back, she herself never expected that dancing would have enriched her life to this magnitude.

Kiki Kovaříková, Czech Republic

Kiki was born in 2003 in the city of Brno (Brünn). She led a regular normal and innocent life until the age of 13, when her older sister by two years, Kaja Kovaříková, surprised Kiki by asking her to attend a weekend folk dance camp in the same town. Excuse me: Folk Dancing? Kiki was certainly much more into disco or something more modern sounding, but in the end, Kája convinced her and the two indeed went. Two guest teachers from Israel were invited for this event called “Machol Brno”, namely Boaz Cohen and Gidi Eiko, both from Jerusalem. As she remembers, her first major difficulties were in differentiating between her left and right foot, more than actually remembering the simple dance sequences she learned in a beginners course she took, the first one she ever attended in Israeli folk dance. As it turned out, it was “love at first sight”: The music, the getting together, the joy and fun. This was not only limited to folk dancing; she eventually also found interest in Judaism and Israel. Together with Kája, Kiki soon joined the local regular weekly Monday Israeli folk dance course, led by Pavla Dvořáková. In addition, she started to study Hebrew in a course offered by the local Jewish Community Center. And in 2017, when she was barely 14, her grandfather took her for a weeklong trip to Israel. Since then, she has never missed an opportunity to visit as many Israeli folk dance camps in Czechia as possible, such as the one in Prague led by Ondrej Novak[1].

Generally, she is a bit disappointed that she does not know a few more of the older dances, even more so, the pioneer dances from the very beginning of Israeli folk dance, as she pointed out. So how can she deliver a fair judgement in comparing the new with the old? Her criticism basically is that at practically all of the camps in Central Europe, for the most part, only the latest choreographies are taught. Younger dancers like herself will thus never be able to properly learn the classics. After graduating from high school in late spring 2021 she would like to study something connected with agriculture, while her sister Kaja is already busy with Jewish Studies at the Palacky University in Olomouc (Olmütz), a distance of just about an hour by car from their hometown.

Elena Moczko, Switzerland

Elena was born in 2002 in the small Upper Bavarian township of Bad Tölz and in 2008, moved to Switzerland (Cantone Zug) with her sister and parents. She soon attended a ballet school for several years, followed by aerobic and jazz dance. Her mother, Christiane, a pharmacist, had already started with Israeli circle dances during her studies in Tübingen (Southern Germany) and later on, in Munich at the JCC’s weekly courses, led by Matti Goldschmidt. When Elena was about twelve years old, her mother suggested that she attend a weekend session in Olten (Cantone Solothurn), led by Oded Harari, who was born in Kibbutz Yehiam (יְחִיעָם), east of Nahariya, and had moved to Berne in 1973. Since Elena was the only young dancer at this event and did not have a clue what to do; she mostly sat around during the workshop and was not really impressed about what the grown-ups did, to say the least.

She gave herself a second chance, however, as her mother again invited, now together with her older sister by two years, Anja, to just another workshop, this time in Winterthur (Cantone Zürich), and again led by Oded Harari. This too did not really convince her. In spite of this, more out of certain boredom, while on summer holiday somewhere in Croatia, her sister, Anja Moczko, decided to teach her Rafi Ziv’s dance, “Mimi”. The music was just perfect in Elena’s eyes (and ears, of course) and from then on she became her own driving force for more. In 2016 her mother booked a place for herself and the two daughters at “Hora Or”, a dance camp in Lille (France) led by Benny Assouline. Back at home, she continued dancing in Zürich, on a more regular basis, at the Jewish Community Center’s weekend sessions of Ronit Bollag and at an annual dance weekend camp near Berne led by Oren Ashkenazi.

She personally prefers the newer dances, which in her eyes are more complex and sportive, and thus more challenging. On the other hand, she is aware that she is still missing a lot of popular dances of the 80’s and 90’s, especially at camps during the evening open sessions. She also complains about the fact, that at camps, too often the invited dance instructors prefer to teach their own dances which are hardly danced in other sessions. During the Corona crisis, she has kept herself updated through YOUTUBE video clips. After a year, as an exchange student in Bretagne (France), Elena graduated from high school in late spring 2021.

Her final paper of 52 pages was about Israeli folk dance and the meaning behind it. Within the framework of this thesis, she not only choreographed on her own two dances with clearly Israeli folk dance-related step combinations; she also described her experiences of teaching several simple Israeli folk dances to a group of 12-13-year old girls, consisting of more than twenty dancers. In the end, each of the young students had to fill in a short questionnaire about what each of them thought or felt about this new experience; something they had never seen or heard about before. The vast majority was positively surprised by how entertaining folk dance can be. It certainly changed their ideas in general about folk dancing.

Elena’s goal for the near future is to study Social Work and hopes to be able to also include here some of her beloved Israeli folk dances.

Nathalie Ivasov, Germany

Nathalie was born in 1994 in Odessa (Ukraine) and until the age of 8 attended a Jewish school, which also included classes in Hebrew. In 2002 the family moved to Germany, first to a small township in Saxonia named Borsdorf, and a year later, to Leipzig. This is precisely the city where some of the acknowledged founders of Israeli folk dance, namely Gurit Kadman and Rivka Sturman, came from. Nathalie’s grandfather was eager to have his granddaughter educated in Jewish culture, so she joined a painting course as well as a singing course at the local JCC. After a few months, this vocal group had its first public performance, by coincidence, together with a performing dance group, “Gvanim”. When she saw the group dancing, Nathalie at once became thrilled and through her grandfather, asked to join this group. Needless to say, the group, with all of its members older than 20, rejected her.

Four years later, in 2007, when Nathalie was 12 years old, she gave it another try. This time the group leader, Galina Kapitanova, accepted her. Even though “Gvanim” used Israeli music for its performances, this was by far not yet Israeli folk dance. In 2012, a good part of the group, with about 12 (female) dancers, decided to take part in a workshop, led by Matti Goldschmidt. This was the time Nathalie had her first real contact with Israeli folk dance and it has never stopped. Since then, she has regularly attended the various camps organized by “Israelisches Tanzhaus” based in Munich, such as “Machol Germania” in Pappenheim (with guest teachers including, in alphabetical order, Ofer Alfasi, Sagi Azran, Dror Davidi, Hila Mukdasi, Eithan Mizrachi, Tamir Scherzer, El’ad Shtammer), the weekend workshops with Israeli choreographers (such as Michael Barzelai, Dudu Barzilai, Itzik Ben Dahan, Yaron Ben-Simhon, Yaron Carmel, Shmulik Gov-Ari, Avi Peretz, Tamir Shalev, Rafi Ziv, and others), and the annual camps for beginners, “Hora Sheleg” over Silvester (New Year).

She visited Israel for the first time in March 2016, through the “Taglit”- aka Birthright-Israel-program. Even though folk dance is not [sic!] part of Taglit’s schedule, the organizers asked her to do some teaching on one evening. Nathalie’s choice of dances were: “Tzadik K’Tamar”, “Od Lo Ahavti Dai”, and “Hora Hadera”. After all, Nathalie had to deal with a totally inexperienced group. In 2019 and 2020 she also completed an Israeli folk dance course led by Tirza Hodes, together with either Lucy Maman or Marina Evel organized by “Zentralwohlfahrtstelle der Juden in Deutschland (ZWST)” in Frankfurt/Main (= Central Welfare Office of the Jews in Germany). Meanwhile, Nathalie changed her citizenship from Ukrainian to German and thus also her name from Natalya Ivasova to Nathalie Ivasov. She left “Gvanim” in June 2020 in order to form her own performing group, “Same’ach” (= happy or “freylach” in Yiddish) with about twenty members. Nathalie was not content with the methodology of leading a performing group as was the case with “Gvanim”. In her opinion, “Gvanim’s” approach was closer to technique and sports and less to dance and especially Israeli folk dance itself. Having become a certified kindergarten teacher (as was, by the way, Rivka Sturman), Nathalie can thus put her own ideas into practice not only in her own performing group, but also in a newly founded children’s group called “Shemesh” (= sun), which consists of about ten members. The local JCC, recognizing Nathalie’s ambition, energy, and talent, has already sent her several times to different public schools, thus, as an ambassador of Israeli folk dance, bringing local non-Jewish school kids closer to dance and Jewish-Israeli culture.

Personally, she prefers the classic Israeli folk dances, since they have, in her opinion, a more folkloristic touch. She heavily criticizes the huge number of modern Israeli dances. No one in the world is able to remember a few hundred new dances per year. Especially, since a high percentage of those are quickly forgotten after only a few months – and too often, never to be danced again. Nathalie’s aspirations, already as an eight-year-old, have so far been successful, in that today she dedicates almost her entire life to Israeli folk dance. This is in addition to the time she needs for her education, which right now, is understandably still her first priority.

Marina Victoria Halsman Serwaczak, Brazil

Marina was born in 2005 in São Paulo, Brazil. Most of her ancestors actually came from Poland. She has danced since her early childhood and cannot even remember a period in her life without dancing. Her first dance steps in the classes she attended belonged to the category of contemporary sacred dancing, which she soon left at the age of four in order to join the local JCC’s dance group for 4 to 8-year old children called, “Parparim Ktanim” (= little butterflies). As the largest Jewish community in Brazil, with 80,000 people, the JCC of São Paulo has not only one or two dance groups, like most of the European Jewish communities, but a dozen or even more. Over the years, Marina climbed the rungs of the dance group ladder: “Parparim Gdolim” (= big butterflies), followed by “Kalanit” (= anemone) and eventually “Lehakat Shalom” (= peace troupe).

By the age of 13 years, she was asked by the management to assist in teaching, as they recognized Marina’s dance talents. Currently, she leads this group together with Carolina Mosseri. She also teaches an adult group, mainly in the age range of 30-70, albeit with a few teenagers participating. Her teaching repertoire does not only include the “latest hits” from Israel such as “Resisim” by Michael Barzelai and Yuval Tabashi, but also Bentzi Tiram’s “Ha’Har Hayarok”, for example, which she recently taught. So far, she has never left Brazil, but she likes to travel and especially to join the relatively large number of local dance events, for, “Festival Carmel”, in her hometown. In 2016 she was asked to join the organizational team for this event. In 2019 she attended a camp called “Machol Brazil”, led by Lucas Schwetz.

Not just another camp and definitely special to Marina is “Festival Hava Netze Bemachol”, which began in 1970 and just celebrated its 50th anniversary in Rio de Janeiro, Nowadays, it is led by André Luiz Grinspan Schor and Sergio Rosenboim. Despite the Covid-19 pandemic they did not give up and in 2020, created the first internet “Festival.com” including a beautiful tribute to the well-known choreographer, Luiz Filipe Barbosa, who passed away that year. For the festival, the organizers invited everyone to submit a dance choreography: Out of twenty-four entries, eight were chosen to be presented for the final at the event itself. Among those final entries was Marina’s choreography (together with Bruna Steinberg) titled, “Oseh Li Tov” to a song by Agam Buchbut, that ranked seventh, a first and fantastic success for the two young ladies.

In early 2021, as an additional teacher, she joined HARKALIVE, a popular and worldwide watched online platform developed by Ilai Szpiezak (London) with various online zoom sessions.

disappointment of manyIn regard to the huge number of Israeli folk dances, she is aware that one has to consciously move with the times. Societies are subject to permanent change and in Marina’s opinion, so too, is Israeli folk dance. Nevertheless, this development can only be appreciated with a sound knowledge of classic and older dances.

Melanie Fröhlich, Austria

Melanie was born in 1994 in Vienna and as far as she can remember, she danced before she was even able to walk. During her time in kindergarten, she took ballet classes for several years – like so many other girls her age. She was lucky enough to have a grandmother, Monika Macht, who loves to dance, and in taking care of her grandchild, Monika simply took Melanie, from the age of three, to all kinds of Israeli folk dance events. The first one Melanie really remembers was a dance camp in Labaroche (Elsass, France) near the German border in the year 2000. This must have been so impressive because to this day, she remembers the names of the invited teachers: Bonny Piha, Yoram Sasson, Haim Vaknin, and Rafi Ziv. Back then, she basically learned most of the dances she knows by watching from the side while simply trying to follow other more experienced dancers.

Soon Melanie joined her grandmother in organizing the dance classes of the latter on Monday nights and Saturday afternoons in Vienna’s “II. Bezirk” or 2nd district, which until WWII was known as the “Jewish district” of Austria’s capital. Should grandma here and there have been prevented from coming, Melanie gladly took over leading the sessions. In 2016, at a dance competition at Machol Hungaria, organized by Gyorgy (Ubul) Forgacs, she won second prize. For years, both Melanie and her grandma, attended many of the dance weekends in Munich, organized by “Israelisches Tanzhaus”, which included choreographers such as Michael Barzelai, Dudu Barzilay, Meir Shem Tov, Avi Levy, and many others. Over the last fifteen years, both also organized their own weekend workshops in Vienna with Sefi Aviv, Eran Bitton, Gadi Bitton, and several others.

She is also a member of the local performing group, “Hava Nagila”, organized as a registered charity, which performs on various Jewish holidays and was even on stage at the European Maccabi Games Vienna 2011 (with a stage choreography by Matti Goldschmidt). Most of Melanie’s spare time is connected to Israeli folk dance. Since there is not one single man available in Vienna, at least not for Israeli folk dance, partner dances are unquestionably not her favorites. Thus, she has enough space to concentrate exclusively on circle and block (or line) dances. She definitely prefers the newer dances with a more Mediterranean touch and more complex step sequences.

Alexandra Pantis, Romania

Alexandra was born in Oradea (Großwardein), Western Romania, in 1999. She started to dance in kindergarten, mainly to Latino rhythms. When she was eleven years old, her mother, recognizing her dance abilities and motivation, suggested that she join a traditionally dressed Romanian dance group, a folk ensemble called ”Florile Bihorului” of which she was a member for eight years. In 2016 she joined yet another traditionally dressed dance group called “Die Regenbogen Tanzgruppe” (= rainbow dance troupe) which concentrates on German motifs, thus the German name of the group.

In fact, connections to Israeli folk dance came only by coincidence. In 2016, after an English class, Ana Cecilia Bucevschi, one of her classmates, started to speak, more in passing, about the local JCC’s dance group “Or Neurim”, led by Futo Ildiko (choreography) and Alexandrina Chelu (management). Alexandra became curious, and after her first Romanian group dissolved and later having joined a second one, namely the “Ansamblul Folcloric “Vetre Bihorene”, she was determined to try something new with a third performing troupe.

The time with “Or Neurim” is split into two sections: One half is used for performances, mostly presented within the framework of Jewish or Israeli holidays, while the other half is reserved for practicing Israeli folk dances. She finds modern Israeli folk dances more challenging, compared to the simpler structure of most of the pioneer dances; even though, as she admits, she hardly knows any of them. She especially likes the feeling of being part of a united dance community, such as in that of Israeli folk dance, which she experienced during the past years when attending, for instance, the 5-day camp, “Machol Hungaria” in Szarvas, a relatively short drive of approximately two hours by car from her hometown. Compared to Israeli folk dance, for instance, there is nothing like “Romanian dances” per se, as Alexandra points out, since they may highly differ in character from area to area. And certainly, there is no such thing as a single Romanian hora. She adds that contrary to all assertions, no Romanian would recognize the Israeli hora as anything Romanian. This is probably to the big disappointment of many Israelis.

Alexandra studies Mathematics and Informatics (computer sciences). She is in her final semester with both majors and would like to pursue a master’s degree so that she can become a mathematics teacher. Parallel to her studies, she is about to complete a two-year course in traditional Romanian dance at the “Francisc Hubic” Art School, consisting of two meetings a week for about two to three hours each. This certainly would create a basis for her also becoming a teacher in the field of dance and, especially Israeli folk dance. She was surprised to hear that couple dances are extremely popular in Israel. She personally prefers staying with circle dances only; the lack of dancing men, not only in Romania, but also in many other countries in Europe, leaves too many women too often sitting around and bored as soon couple dances are played.

Heta Heinonen, Finland

Heta was born in 1999 in Vaasa, a university town approximately 440 km (274 miles) north of Helsinki, with roughly 60,000 inhabitants. (25% of them are Swedish speaking.) By the age of six, she joined a ballet class for children, accompanied by the usual dance performances for the parents at Christmas and in the spring. A couple of years later, her dance classes also included hip-hop and modern dance. Her first contact with Israeli folk dance occured in 2007, when she joined her mother, Elisa, for a weekend seminar in Helsinki, the capital of Finland, led by Yaron Meishar.

Here is the place to add that Elisa Heinonen started with Israeli folk dance more than twenty years earlier, first with Wim van ser Kooji, who is originally from the Netherlands, but moved to Finland in the early 1970’s. In the years that followed, she also danced Israeli folk dance with Leena Jäppilä and Alpo Pajunen, the father of Jouni Pajunen who nowadays is teaching Israeli folk dance who met Noriane’s mother

n Finland. So it seemed only natural that Heta followed in her mother’s footsteps. Heta feels that dance is an integral part of her body. It’s in her blood. She felt, that (after having practiced other styles) this new style of dance, namely circle dances, made her feel good. All in all, she never had a real opportunity to join regular, that is weekly dance sessions, but liked to move from camp to camp including Machol Czechia in 2011, Machol Europa and Machol Baltika in 2013, and Machol Hungaria three times. She would never sit around at a camp, simply trying to copy the step sequences of dances from others that were not taught during a camp. And admittedly, there are quite a lot of these that are done at the evening sessions.

During the years 2016 – 2018, Heta was asked by a church group in a town called Seinäjoki, a one-hour drive south-east of Vaasa (80 km), to teach dances for beginners. Basically, she has no real preference for old or new or, for instance, dances to oriental music. She likes the challenge, “the quicker, the more fun”, as she disarmingly relates. Definitely a big plus, in her opinion, is the feeling of dancing together with dozens of people from other countries, at least at Israeli folk dance camps, and the fact that she would be able to join as many dances sessions as possible around the world with the knowledge of dances she meanwhile absorbed, not to forget her talent for picking up step sequences quickly. Heta currently studies Energy Technology in Espoo, the second-largest city in Finland, and keeps herself in shape dancewise through ballet classes.

Dominyka Chackelevic, Lithuania

Dominyka was born in 2002 in Vilnius (Wilna). From her earliest childhood, she has seen herself as a professional dancer, having started with ballet by the age of six. She certainly did not waste her time spending her free time after school for some pleasurable recreation: The youngsters already danced for two hours five times a week. The courses included rehearsals for public performances and later on, even the participation in several competitions in countries like Latvia or Russia. Israeli folk dance appeared relatively late in Dominyka’s life. Probably the reason was that her mother Rita Chackelevic used to play Israeli music exclusively during car rides, that is, mostly music for which a certain dance sequence was choreographed. At first, she did not want to believe that a different sequence of steps was needed for each tune.

In other words, Dominyka grew up with the right music in her ears and in the end she had her first real contact with Israeli folk dances at the age of 12, when her mother took her to a camp in Milan (Italy), namely “Stage Yofi Aviv”, organized by Roberto Bagnoli and Yehuda Rahmani and with the instructors, Dudu Barzilay and Avi Levy. As an already skilled dancer, she had no problems following the workshops for advanced Israeli folk dancers. Just a few years later, she joined the weekly classes of her mother and also taught Israeli line dances in the Jewish summer camps of the Baltic states (Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia). Absolute highlights for her were the family holidays in Israel where she and her mother followed as many public beach dance sessions as possible – such as on Saturdays at Gordon Beach in Tel Aviv.

In fall 2018 her mother, together with Elena Gorelik, organized in Vilnius the 3-day camp “LeRikud” with Dominyka greatly supporting them from behind the scenes. At the moment, she studies dance at Middlesex University in London, which naturally not only includes dancing itself, but also subjects such as anatomy and dance history. Within the framework of these studies, one of her papers was about Israeli folk dance, titled “The History and Creation of Israeli Folk Dance and Its Relation to Dance Therapy”. Being that she knows about several different regular Israeli folk dance classes in London, she is eager for the Corona-related restrictions to be lifted for dance sessions in England to return to normal operation.

When she was young (well, at least younger than the 19 she is right now), she definitely preferred Israeli folk dances to modern music. Over the years, however, she became aware that the construction of a house does not start with the second floor. Especially the music of the early dances draws her attention and, after all, Dominyka is convinced that the Israeli folk dances of today would look different without the foundation laid by the zero generation of Israeli folk dance. Last but not least, to quote from Dominyka’s paper: “It is Israeli dance which infuses emotions and goals into my daily life. When I dance, I forget everything, I feel freedom.”

Iris Pinto, Turkey

Iris was born in 1997 in Istanbul. Parallel to entering first grade, she also started with her first dance steps by joining a children’s ballet school, but decided to drop out after less than two years, bec because uase she felt too shy to express herself through her body and simply felt too uncomfortable to continue. Instead, she joined a Saturday and Sunday program at the Jewish Community Center, thus meeting other kids and learning more about Jewish life.

These new programs were mainly introduced by her grandfather who had studied a few years in Israel, and who also brought with him the idea of folk dancing to a community of around 20,000, by far the largest in Turkey. Her father already used to do some Israeli folk dancing, keeping with the classics of Israeli folk dance, and especially preparing conventional dance performances for the celebration of Jewish holidays. This group, which still performs today, is called “Shemesh Karmiel” and was definitely for the “old people”, that is, those over 30. It was led by Verda Darsa with lots of support by Shlomo Maman.

On the other hand, Iris meanwhile had joined by the age of around twelve, the folk dance group for the young ones, with Valeri Bahar being one of the leading instructors. At different times, this dance class attracted between fifteen to twenty people, and since 2010, the JCC sends a small delegation every year to Maurice Stone’s “Machol Europa”. Iris’ turn was in 2014 and she was amazed at the quantity of the dances danced in the evening sessions: The roughly one hundred dances she knew from home were hardly played. As a result, she could hardly dance at the evening sessions, even though at home she was considered to be one of the more advanced dancers, based on the number of dances she knew.

In 2015, turning just about 18, she moved to Chicago to study Psychology and Cognitive Science at Northwestern University. It took her a whole year to adjust to the environment without any dancing, and on a visit home in 2016, she attended her second camp, namely, Machol Hungaria, led by Gyorgy “Ubul” Forgacs. Back in the United States, Phil Moss highly recommended that she should try his own camp, “Machol Merkaz”. This seemed to have been a certain turning point for her. Since then she regularly visited, not only the weekly classes of Phil Moss, but until her return to Istanbul in fall 2020, also those of Bruria Cohen. Iris even attended an additional camp, namely the one in Boston called “Yad BeYad”, led by a team of three: Ronnie Efrat, Yehuda Vishny, and Rina Wagman. Her own efforts, together with a fellow student, to introduce Israeli folk dance directly on the campus and financially supported by Hillel, the largest Jewish campus organization in the world, had to be discontinued after almost two years, due to the lack of regular participation.

The only way to stay connected during Corona times is through online sessions, in particular Ilai Szpiezak’s “Harkalive”, broadcast from London. In order not to forget the steps and to stay in practice, Iris thus dances in her home on her own. She loves the variety of the music and step sequences in Israeli folk dance, and the diversity of the types of dances. Certainly, she would have preferred the community feeling and being able to get together.

On the other hand, she recognizes that these online sessions have something that got lost in the old and regular dance events: Firstly, for instance, dance titles are announced. How can someone without proper knowledge of Hebrew ever remember the dance titles when they are never spoken out loud. Secondly, there mostly is a break between the dances, which gives time to breathe. And thirdly, at least in Ilai’s classes, often the name of the choreographer or a little anecdote about the specific dance is added. She is aware that contrary to her own development in dancing, it is difficult to inspire young kids to engage in Israeli folk dance. Iris enjoys the challenge of learning new dances, but misses the Israeli debkas, which were so popular in the 1970s and 80s.

Rebeka Grosová, Denmark

Rebeka was born in 2000 in Liberec (Reichenberg, Czech Republic) and moved with her family in 2014 to Copenhagen, the capital of Denmark. She started to dance ballet and theatrical dance at the age of six. Her first steps in Israeli folk dance began four years later for a period of about three years, since her mother, Andrea Grosová, was already involved with this genre. However, one of the reasons for her to move to Denmark in her teens was the idea, after having received a scholarship from a private school, to concentrate more on jazz dance and musicals to become a professional dancer.

Rebeka’s return to Israeli folk dance took place in 2019, when the whole family decided to attend Machol Czechia. This inspired her so much, that she also joined Machol Europa as well as Machol Hungaria the same year. One thing she especially liked in England was the tighter and disciplined program, which also included practicing for a dance performance. Meanwhile, she studies modern dance at the “Sceneindgangen Versatile Dance Education” in Copenhagen. Unfortunately, Denmark does not seem to be the place for establishing a regular Israeli folk dance session, as she sadly mentioned. On the other hand, she would try to dance as much Israeli folk dance as possible, as soon as time and money allow it. And certainly, as a professional dancer, she favors more modern dances with a bit of a challenge. Nevertheless, in order to preserve Jewish history, the pioneer dances are equally important for her to know.

Polina Sotnikova, Russia

Polina was born in 2000 in Perm (Russia) and danced from her early childhood, which included modern and classical dance. Being a member of a dance competition team called “Konfieti” (= sweets), she had the chance to travel to countries like Finland, Germany, Montenegro, and Sweden. While she studied Spanish and English at the university, her aunt, Olga Vatletsova, recommended that she should try Israeli folk dancing and actually sent her in 2019 to Machol Europa in Coventry (England); Polina would surely like it. Olga herself had attended this camp in England several times, the first time being in 1994.

For Polina, this was the first time ever for her to get in touch with Israeli folk dance. The experience to learn over two dozen dances within only four days overwhelmed her emotionally, needless to add that as an experienced dancer, she had no real problems following the teaching and remembering all the dances. With this basic knowledge, she certainly wanted to continue and planned to found and organize an Israeli folk dance circle back in her hometown, since this kind of dancing was unknown there. Sadly, because of Corona restrictions, this idea had to be delayed for the time being.

Olya Spektorova, Crimean Republic

Olya was born in Simferopol in 1991, the capital of the Krim peninsula, then part of Ukraine, and since 2014, ceded to the Russian Federation. Like many children her age, she started to take some dance classes at the age of three for four years, mainly in the “socal dance” field. This was followed by a huge break for her in the field of dancing until she finished high school when, at the age of 17, she joined a performing dance troupe. Five years later she decided to enter a “Masa” program. Masa is funded by the Israeli government and the Jewish Agency (sochnut), with fifty percent by each. Thus she moved to Tel Aviv for half a year, enhancing her resume with international work experience in structural engineering. Even though back home she had prepared herself for this program with two years of studying Hebrew, her knowledge of the language was not really good enough for proper conversations. So she was lucky that the mother tongue of her instructors was – nowadays not a real coincidence – Russian.

After having returned to her hometown with a new kind of Jewish sense of mission, she joined the Jewish community’s “Hillel” group, consisting of people age 16-26. They met once a week, normally on Shabbat. Their program also included dancing, albeit here to Eastern European Jewish ethnic dance motifs and music. As Olya pointed out, the Jewish community had kind of a basic repertoire of eight to ten pioneer circle dances, which never had the term “Israeli folk dances” attached to them – it was simply considered to be Jewish. Upon an invitation of Maurice Stone in 2017, the leader of the Hillel group decided to send Olya to England to join the 40th “Machol Europa”. This was actually the first time ever she got in touch with Israeli folk dance. Olya simply never had heard about this before.

After this two-week experience in Coventry, England, she succeeded to introduce a few of the dances she had learned there in a Hillel class that was then led by Aleksandra Gorelik. With the outbreak of the pandemic, however, Aleksandra had left the group and everything died down. Olya loves Israeli folk dance because it connects her not only to Israel as a country, but also to the Hebrew language that she would love to speak much better, and mostly because Israeli folk dance simply creates a kind of togetherness she had not experienced before. Unfortunately, there is currently a lack of younger people in the much too small Jewish community of Simferopol who would make the establishmet of a new dance circle possible – a dance circle she would be more than happy to lead.

Noriane Lerouge, France

Noriane was born in Laval (Britanny) near Rennes in 1998, a small town with a population of roughly 50,000 in the northwest of France. She believes that she started to dance Israeli folk dance by the age of around three months, since her father is the dance instructor and choreographer Frederic Lerouge, who, met Noriane’s mother, Solveig, where else than, of course, at an Israeli folk dance camp. Solveig again grew up in a hamlet called Roqueredond (near Montpellier) in the south of France, together with the family of Vincent Parodi. By the age of three, Noriane began ballet classes, followed by contemporary and modern dance. As a teen, she joined her father as his partner for salsa, tango and rock sessions.

At home, folk music was mostly played, which certainly shaped her and her younger sister Maïvenn’s musical subconsciousness forever. At dance camps, Noriane was always a little star. At an early age, camp participants took her by the hand to join the circle – and made her try to follow, at least the directions, as much as possible. The first Israeli folk dance camp in which she she actively and determinedly participated was at the age of 10 in Aubigny, led by Benny Asouline, when she began to make notes, like writing down dance names in Hebrew and French or even step sequences. Noraine still owns this notebook. The camp in Aubigny was followed by several dozens of other dance camps over the years. By the age of 17, after having received her baccalauréat (= high school diploma), she moved to Nantes, where she joined a regular Israeli folk dance class led by Odile Hervy. Soon after, Noraine also did some teaching in support of Odile. As she admitted, the choice of the dances she taught was higly influenced by the music she found appealing.

In the framework of her studies, namely Comparative Literature (English and French) she moved, for one year, to Edmonton, the capital of Alberta (Canada). One of the reasons to have chosen Edmonton of all places, was the existence of regular dance sessions, then led by Meirav Or at the local JCC. Noraine was surprised how quickly she became accepted in this Jewish environment as a non-Jewish dancer. In France, as in many other west European countries, Israeli folk dance is in general not an integral part of Jewish life, at least not the kind of Israeli folk dance as it would be defined here. It rather appears in a secular non-Jewish social environment.

After a year abroad, Noriane moved back to France, namely, to Nantes and then to Lyon finishing her studies to become a high school teacher. Certainly, the Covid-19 pandemic affected her dance aspirations, but she never stopped dancing, even if the chosen dance space would have been only her living room. Nowadays she lives in the alpine town of Chambéry (population roughly 60,000), south of Geneve and east of Lyon, working as a school teacher. There she joined an Israeli folk dance class regularly attended by around 25 participants. About the flood of new dances introduced each year she shrugged her shoulders. The best will “survive” – while she likes “well-structured” dances the most. However, she is aware that she still misses many of the classic dances, since they all are older than herself, as she points out. Just recently she taught herself “Shir” from the internet. A huge part of her social life is based on or the result of being involved with Israeli folk dance: “I simply would not be myself without those dances”, she said.

Natalia Hakenberg, Poland

Natalia was born in 1990 in the city of Gliwice (Gleiwitz, Upper Silesia), the place where on August 31st, 1939, the German “Schutzstaffel” (SS) faked an allegedly Polish-led attack on the local radio station which served for the Nazis as a pretext to invade Poland – the beginning of World War II. Surprisingly, dance of any kind was not an issue for the family until they moved to Warsaw in 2002. Soon after, Natalia’s father overheard by coincidence an announcement made by the leader of an already existing Israeli folk dance group called “Snunit” (= swallow), led by Monika Leszczyńska, who was looking for new members in her group. As a result, Natalia’s mother, Lucina Hakenberg, a sports teacher, took her, then 12-year-old, and her elder sister, Miriam Hakenberg, to the class, where they learned dances like “Hora Hadera” and “Kleizmer”.

Natalia liked not only the music. She was especially impressed by the whole atmosphere of unity and happiness that everyone radiated, of holding hands (in Israel, long since “out-of-fashion”), of following set step sequences instead of improvising, which Natalia in fact disliked. Since she was still considered to be too young for regular attendance at the class, Miriam and her mother nevertheless joined and retaught the new dances back home. In 2003 Miriam returned from Machol Hungaria and familiarized Natalia with more modern Israeli folk dances. From 2004 on, now being 14 years old, she finally started to join the regular weekly “Snunit” dance class. The first dance camp she ever attended was in 2007, organized by the same dance group in the small town of Śródborów, just a few kilometres southeast of Warsaw, with guest teacher Boaz Cohen. The experience of having learned new dances from a genuine Israeli dance instructor and having participated in such an event strengthened her focus on Israeli folk dance.

Natalia continued to learn as many dances as possible through videotapes, as filmed at Machol Hungaria or the Munich workshops, in addition to YOUTUBE videoclips.

Her physical education teacher allowed her to teach Israeli dancing to classmates for a whole hour once a week. At the same time, she also started to occasionally teach the “Snunit” dance group. Furthermore, she took Hebrew language classes. Her first visit to Israel was in 2010 with a Polish youth group, participating in the project, “Living Bridge Poland-Israel”. This was followed by another two-week trip to Israel in 2012, with the emphasis and only goal to dance as much as possible. Instead, to recover from studies, Natalia actually led an “exhausting life” during the fortnight in Israel, as her daily schedule became: Dancing until after midnight, getting back to the hostel, sleeping until 11 am, packing the rucksack, travelling to a new place and trying to arrive as quickly as possible to the new dance session, preferably from the very beginning with the basic dance repertoire.

In 2013 Natalia started with her studies in “Management” at the Warsaw University of Life Sciences. In the same year, the Hakenberg family also began to organize their Israeli folk dance camps named “Polin Rokedet” (= Poland dances). During the years until 2021, it was held eight times in different locations (with the exception of 2020 when an online live broadcast was organized). Invited dance teachers and choreographers included Oren and Lena Ashkenazi, Yuval Tabashi, Bonny Piha, Avi Levy, Elad Shtamer, Hila Mukdasi, Yaron Elfasi, Ilai Szpiezak and Michael Barzilai. In 2014 she graduated from the Course For Israeli Folk Dance Instructors (“Ulpan”) in Israel. She never felt too tired to also travel abroad and visited places like, just to name a few, Munich in 2010 with guest teacher Gadi Bitton (organized by “Israelisches Tanzhaus”), Machol Hungaria in 2011, with guest teachers Eran Bitton and Yaron Carmel, Riga in 2012 with Avi Levy, Leipzig (Germany) in 2015 with Dudu Barzilay and Vilna in 2018 with Rafi Ziv.

While working for a hig-tech company in Gdansk on the Baltic Sea from 2017 – 2019, she led a local dance group. With the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, dancing also became difficult in Poland. With proper knowledge of Hebrew, in late summer 2021, she moved, so far temporarily, to Tel Aviv working in a Polish-Israeli recruitment agency, again providing her with the opportunity to dance at Israeli folk dance sessions almost all over the country. In principle, she likes both, older and new dances. In older dances, however, Natalia likes the fact that there is more holding hands and thus a more intense feeling of togetherness. On the other hand, in general, she would rather not pay too much attention to the creation date of a dance as long as she feels somehow connected to the steps and music.

In regard to the enormous number of newly created dances, Natalia tries to see the positive side: This way dancers may have a larger choice to find the dances they favor. And if a dancer would rather stop putting the pressure on himself to learn all the dances, he or she would certainly find more joy in Israeli folk dancing. Last but not least, Natalia sees in Israeli folk dance, not only the opportunity to find amazing friends throughout the world; her personal gain was to become a more open and more assertive person through Israeli folk dance.

————-

INTRO AND SIDEBARS FOR ANNA

Intro:

And it is certainly noteworthy that not all of those interviewed are Jewish. Nevertheless, they without doubt belong to the worldwide network of Israeli folk dance – a situation the founders of Israeli folk dance, some eighty years ago, most probably never expected.

Sidebar 1:

It was highly important to her to do her own teaching and also include the dance material she liked without being outvoted by others.

Sidebar 2:

The course also emphasized the inclusion of the so-called Israeli folk dance pioneer dances.

Sidebar 3:

She started without any dance experience entering the Israeli folk dance scene through prayer.

Sidebar 4:

The music, the getting together, the joy and fun. This was not only limited to folk dancing; she eventually also found interest in Judaism and Israel.

Sidebar 5:

She is aware that she is still missing a lot of popular dances of the 80’s and 90’s, especially at camps during the evening open sessions.

Sidebar 6:

Even though folk dance is not part Taglit’s schedule, the organizers asked her to do some teaching on one evening. Nathalie’s choice of dances were: “Tzadik K’Tamar” and “Od Lo Ahavti Dai”.

Sidebar 7:

The JCC of São Paulo has not only one or two dance groups, like most of the European Jewish communities, but a dozen or even more.

Sidebar 8:

She definitely prefers the newer dances with a more Mediterranean touch and more complex step sequences.

Sidebar 9:

She especially likes the feeling of being part of a united dance community, such as in that of Israeli folk dance.

Sidebar 10:

Definitely a big plus, in her opinion, is the feeling of dancing together with dozens of people from other countries, at least at Israeli folk dance camps, and the fact that she would be able to join as many dances sessions as possible around the world.

Sidebar 11:

“It is Israeli dance which infuses emotions and goals into my daily life. When I dance, I forget everything, I feel freedom.”

Sidebar 12:

She enjoys the challenge of learning new dances, but misses the Israeli debkas, which were so popular in the 1970s and 80s.

Sidebar 13:

She favors more modern dances with a bit of a challenge. Nevertheless, in order to preserve Jewish history, the pioneer dances are equally important for her to know.

Sidebar 14:

With this basic knowledge, she certainly wanted to continue and planned to found and organize an Israeli folk dance circle back in her hometown.

Sidebar 15:

She loves Israeli folk dance because it connects her not only to Israel as a country, but also to the Hebrew language that she would love to speak much better, and mostly because Israeli folk dance simply creates a kind of togetherness she had not experienced before.

Sidebar 16:

A huge part of her social life is based on or the result of being involved with Israeli folk dance: “I simply would not be myself without those dances”, she said.

Sidebar 17:

She was especially impressed by the whole atmosphere of unity and happiness that everyone radiated, of holding hands (in Israel, long since “out-of-fashion”), of following set step sequences instead of improvising, which Natalia in fact disliked.

Key to flags and countries

| 01 | Natalie Assa | Bulgaria |

| 02 | Melu Laniado | Argentina |

| 03 | Agnieszka Kanas | Poland |

| 04 | Kiki Kovaříková | Czechia |

| 05 | Elena Moczko | Switzerland |

| 06 | Nathalie Ivasov | Germany |

| 07 | Marina Halsman Serwaczak | Brazil |

| 08 | Melanie Fröhlich | Austria |

| 09 | Alexandra Pantis | Romania |

| 10 | Heta Heinonen | Finland |

| 11 | Dominyka Chackelevic | Lithuania |

| 12 | Iris Pinto | Turkey |

| 13 | Rebeka Grosová | Denmark |

| 14 | Polina Sotnikova | Russia |

| 15 | Olya Spektorova | Krim Peninsula |

| 16 | Noriane Lerouge | France |

| 17 | Natalia Hakenberg | Poland |

[1] Compare my article: “July 2018: 20 Years of Machol Czechia”, in: Rokdim-Nirkoda (2019), no. 101, 32-35.

Comments

התראות